In David Brooks’ Ted Talk, “The Lies Our Culture Tells Us About What Matters,” he defines the differences between sufferers who break, and sufferers who break open. Those who break open turn into “weavers,” people who use their struggles to repair our nation’s social fabric, working to end loneliness and isolation.

This week, Indy Maven talks to a master weaver: Britt Sutton, CEO of ArtMix, a local organization that works to transform lives of people with disabilities through art. A decade ago, while a student at Indiana University, Britt suffered a grand mal seizure on a hiking trip that changed her life—and put her on a path to make sure that people who have disabilities have the chance to express themselves creatively, and be heard and understood.

It’s obvious from reading your ADA 30th anniversary essay for the Indiana Arts Commission that your career has a deep sense of purpose. How did this all begin?

I was with my family on a hiking trip, and I just did not feel right that day; something was definitely off. I sat down, and it was just pure luck that my sister sat down right behind me. I fell backwards and had my first grand mal seizure. It was 2009, I was in a sorority at IU, loving college life, and it was just, BAM—now you have epilepsy. It was devastating. I am a classically trained dancer, and the medications threw off my equilibrium. Arts, theater, dance, performance—these things were my life—and suddenly I could not complete a pirouette without losing my balance.

I was diagnosed with a genetic form of epilepsy, which explained so many things which had always bothered me. I have always been very sound sensitive, and I started getting really bad headaches in middle school. I would kind of “flake out” sometimes, and I called them my “glitches.” I would be standing in line in the lunchroom, and I would just drop my tray and food spilled everywhere! Now I know my aura: I see spots, and my hands and lips go numb. I realize now that I was experiencing absence seizures.

What was that like as a college student?

I didn’t want to tell anyone. I was embarrassed, and I feared what I call the “B word:” Burden. When you’re in college, you’re striving to be fiercely independent, and what I feared most, and what many people with chronic health conditions fear, is becoming a burden. But I had a seizure in the front room of the sorority house, so I didn’t have a choice but to share my diagnosis. I now know communicating about my diagnosis is about safety and empowering those around me to be aware.

I have the best parents, and my mother encouraged me to go to therapy and talk to a counselor. I felt like what I had planned for life was drastically changed by my diagnosis, and I was devastated. My counselor asked if I had considered doing something to benefit the epileptic community, so I took an internship with an epilepsy foundation. It changed my life.

So you have these challenges, and you’ve taken this internship, then what happened?

I graduated from college as a behavioral therapist and began working with children who have autism. Because of my background with sound sensitivity, and feeling misunderstood with my disability, I found I could connect with children who traditionally struggled to be understood. I became very passionate about working with kids who have autism. From there I fell in love with working with those who have intellectual and/or physical disabilities, and I felt, and still feel, very connected to them.

I had a little guy in my work who I loved with all my heart, and he struggled with communication as he was, at that time, nonverbal. One day he crawled into my lap, and we rocked together as I sang songs from “The Sound of Music.” He calmed down and rubbed my cheek, and in my heart I knew, art could be a bridge for people who don’t feel heard. In our souls, in the core of our beings, we all want to be heard and understood. So often people misunderstand those with autism as not having feelings, but in reality, it’s very much the opposite. Those with autism have just as many feelings as everyone else, but they cannot be understood in a traditional sense.

From this rewarding job, which you loved, you then headed to law school? How did that come about?

It’s because of the same patient! My little guy who loved music was my patient before Medicaid covered ABA therapy. He was making so much progress when his parents came to me and admitted they could no longer afford this very effective, but very expensive, form of therapy. I looked at his mom right in the eye and said, “That’s it. I’m going to law school.” I always knew I would use my degree to study and write disability policy, and that I would go forward working with those with disabilities.

Do you find that some of the old stereotypes of epilepsy still remain?

This is where we must be so grateful for the Americans With Disabilities Act! As recent as 1980, some states wouldn’t allow people with epilepsy to legally marry. I have chipped teeth from well-meaning people who tried to intervene when I was having a seizure. These facts are why it’s so important for things like ArtMix to exist. By creating art side-by-side, and by educating people about disabilities, we can create communities where everyone is heard and understood.

You’ve been quoted as saying “When you meet one person with a disability, you’ve met one person with a disability.”

This statement is true across the spectrum of disabilities, but it seems especially prevalent in the autism community. We look at a diagnosis sheet and our brains are wired to fit people into categories based on what we know to be true of just that one diagnosis. But everyone with disabilities has differing comorbidities, strengths, and gifts; you cannot generalize disabilities into deciding what someone will be like. This wisdom is most needed when communicating with people about autism.

Tell us about ArtMix, and some of your favorite things about working there.

Some of my favorite moments are hearing from the parents who never dreamed their children would experience the joy of having a career. These are true, trained-in-a-trade artists, earning a real wage, and when their families get to see the pride and sense of accomplishment that comes from having real employment, it makes my job such a joy.

How has your organization been impacted by COVID-19?

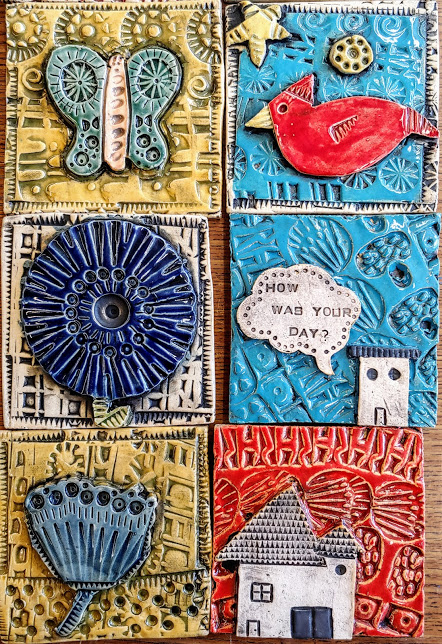

A lot of our artists are immunocompromised, so our organization has been impacted from every possible angle. Our biggest program is our Urban Artists program, and not being able to go into schools and teach kids how they can make a real living in the arts, has been hard on all of us. We have made, I hope, a successful move into 2D art, classes over Zoom, and classes on YouTube. Our gallery is also available for online shopping.

How can members of Indy Maven connect with and support ArtMix?

Take a class! Inclusion means our art classes are for everyone. We’re located inside the Harrison Center for the Arts, which is just a really cool place to take classes. Consider buying our artists’ work (we do commissioned work) and following us on social media. And please consider making a donation and/or sponsoring our reopening efforts. We’re a very small organization, and we must implement the same safety measures you see in larger institutions.

We’re so inspired by how you took a life-changing diagnosis, and used it to create a career.

My experience with epilepsy taught me an important lesson: When I lost “what” I thought I would become, I realized “who” I wanted to become had not changed. Who we become is far more important to the world than what we become. I followed my passions and it has led me to a career I love so much.