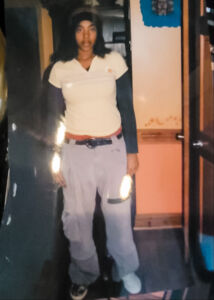

In the spring of 2007, I butterflied. Since the beginning of 8th grade, I noticed a difference in the attention I got from peers and teachers. One teacher in particular, Ms. Whitaker, asked me earlier that school year, “Dallas, how’d you lose all that weight?”

I didn’t tell her that I stopped drinking this flavored seltzer water that screwed up my metabolism and probably hormones. After going to the doctor for weight gain and being told if I continued like this I could get diabetes, being left in the room with just my younger sister and crying to her, “I don’t want to die!” That I ate salad three times a week for dinner, walked circles around the parked car 5 times before getting inside because “extra steps count” and marched in place while I brushed my teeth for the same reason. No.

I just said, “Basketball” as I watched her scan me.

Of course, the sport helped, but I’d learned as a 200-pound Black girl in the South that adults could be cruel about my body and there wasn’t much I could do. So I was cautious with this attention.

And the caution with Ms. Whitaker felt wrong. I idolized her. She was my 7th and 8th-grade math teacher. She had beautiful dark skin, a powerful voice, we had fun in her class, but she was no joke. She’d go from laughing with us to waiting for the correct answer with her arms crossed at the front of the room, muscles visible. She knew math! The bane of my existence and a subject I struggled with throughout high school. I also felt indebted to Ms. Whitaker. She knew I understood math concepts, but struggled in my calculations. So she changed the end-of-year exam, in 7th grade, from solving algebraic problems to explaining how to work them out. I aced that exam. In 8th grade, I was still not good at math, but I trusted this teacher. Spring was looking up! The year was almost done, and Ms. Whitaker had just announced that our class would be taking a field trip to a local amusement park in a few weeks as a reward for our hard work. I was feeling light.

But adults have a way of casting shadows. At the end of one school day, I was passing time before a sports practice, carrying science homework printouts, when Ms. Whitaker approached me. We were in the hexagonal junction of the high school building and the middle school building, the neck of a “T” shape, if you will.

“Dallas,” she said, crossing her big arms.

“Yes ma’am?” I became hyper-aware of the emptiness of the high school building to my back and the distance of the middle school building behind Ms. Whitaker.

“I heard your friend Jennifer likes girls.” An icy-hot feeling shot through my chest and throat. ”I’m coming to make sure that’s not true, cause I don’t want any problems on our field trip.”

I panicked. Jennifer was very clearly gay. I couldn’t imagine any adult sanely thinking she didn’t like girls. She had a girlfriend, everyone knew that. Ms. Whitaker knew Jenn and I were obviously going to be each other’s field trip buddies, too. We were always together during the school day. Why would liking girls be a problem? Were boys who liked girls not coming? Would Jennifer’s parents be called? Why would my teacher put me in this position, alone, at the end of a school day?

“No, she doesn’t like girls.” I made sure to not speak too quickly, but also not look like I was thinking too much. I lied with confidence from behind the shield of science homework protecting my heart.

I looked my teacher in her eyes, trying to communicate a second lie, one I still think is untrue for both Mrs. Whitaker and myself.

“I don’t like girls either.”

Dallas is a land steward, educator, and mother to 3 four-legged children. You can find her in the woods talking to small beetles on blades of grass or drumming up barter circles amongst Black women in Indianapolis. Follow Dallas on Tiktok and Instagram.

All of our content—including this article—is completely free. However, we’d love it if you would please consider supporting our journalism with an Indy Maven membership.