It was a typical Thursday — June 29, 1995.

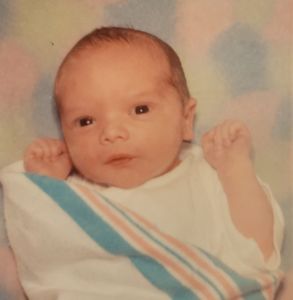

Kristine Bunch drove from her trailer home in Decatur County, Indiana, to Versailles, where she attended machinist and welding courses at a technical institute. She was hoping to get hired at a factory; they’d give her the benefits she needed to take care of her 3-year-old son, Anthony.

A single mother at the tender age of 21, Bunch hustled to make ends meet for her child. Work, school, Tony — a simple life, day after day.

Sunlight bled through the windows of Bunch’s mobile home on Friday morning — June 30, 1995.

Bunch awoke to a hazy fog. Every hint of light was blocked. Nothing clicked in that fleeting moment of grogginess, but her senses sped up. She realized it was not fog that she was seeing — it was smoke.

She immediately ran to Tony’s bedroom door. The absent light appeared in ribbons of red and orange.

“I couldn’t get in because there were flames in his doorway,” Bunch said. “I ran out the front door, took his tricycle, busted out a window, and tried to crawl through that window.”

Bunch’s neighbors heard her screams and pulled her out from the window frame. They called the fire department and told her to wait. She tried running back through the front door, but the fire was already through the roof, and the neighbors wouldn’t relent.

To Bunch, it seemed that she waited at her doorstep for hours. In real time, it was only minutes before firefighters arrived. The police followed two hours later, quickly determining that what had occurred was arson. At 11 p.m. that same day, the police called Bunch to the station. Expecting a lead on who could have committed the crime, she was bombarded with questions about her insurance.

She was only 21, she couldn’t even afford insurance on her car, let alone homeowner’s or life insurance. If the police didn’t have news, what could they want from her?

Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, Bunch spent her last days of freedom planning her son’s funeral and buying an outfit for that funeral. Cold and unresponsive towards everything around her, the last 120 hours of life as she knew it was a blur.

Six days after the fire, on July 5, 1995, Bunch was arrested for arson and the felony murder of her son.

“You don’t think that you can lose everything and they can still find more to do to you,” Bunch said.

Nothing was or would ever be typical again from that day forward. As Bunch’s worst nightmare held her captive, the 17-year fight to prove her innocence began.

***

Sharp odors of mildew and sweat caressed the muggy air as a Decatur County Jail guard walked Bunch to her first concrete cage. An unfriendly bunk greeted her, and she sat, browsing her new home.

An ancient payphone, barred windows, and metal everything — Bunch leaned back against the cinder blocks, painfully surveying the lay of the land.

Aside from women who rotated in and out from drunk and disorderly charges on weekends, Bunch was the sole female in the jail. No one could empathize with what she was going through, let alone with losing a child at such a young age.

Metal tables bolted to the common room floors with attached metal stools framed the confines for dining, which for Bunch meant moldy bread and green baloney. She believed much of the food offered was inedible.

“They don’t want to serve good food to a baby killer,” Bunch said. “A lot of times, I would wait and just hand that tray back and go back to bed because literally, I didn’t care if I woke up.”

Bunch existed within county jail from July to October 1995 and February to March 1996. On April Fools’ Day, she was convicted and concurrently sentenced — 60 years for murder, 50 for arson — and sent to the Indiana Women’s Prison.

During her trial in February, William Kinard, a U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) forensic analyst, testified under oath that he had found “a heavy petroleum distillate” in flooring samples taken from spots in her trailer home where the fire was assumed to have been first ignited.

No ATF documents backing up Kinard’s testimony were given to Bunch’s trial counsel prior, and no file proving the absence of any heavy petroleum distillate existed, at least to the defense’s knowledge.

Jurors believed Kinard and the prosecution’s witnesses. Bunch’s defense team testified that the fire should’ve been ruled undetermined due to the chances of it being accidental. But even as Bunch suffered through what were later proved to be Kinard’s false certainties in court, hope never left her.

Right before her trial, a quiet voice surfaced in her mind. It grew louder and told her she knew what was true, and to stay in this battle, because in due time, she would be a mother again.

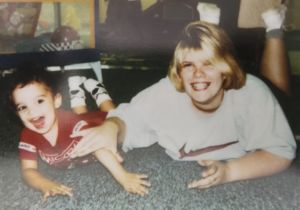

“That was the moment [finding out she was pregnant with Trent] I realized I had something else to fight for, something else to keep pushing forward,” Bunch said. “He was the driving force behind my stubbornness and determination to not give up.”

***

“Better” was not the word for Bunch’s life inside the maximum-security facility, but it was a life that presented opportunity.

Right when she got there at six and a half months pregnant, a woman who had been sentenced to 110 years sought Bunch out — sneaking her pickles here and there to compensate for the prison’s lack of pregnancy cravings. Bunch told the woman that she was going to fight her sentences because she was innocent.

“You know, everybody says they’re innocent,” Bunch recalled the woman saying to her. “I’m going to tell you, actions speak louder than words, so you can either do the time, or let the time do you.”

Bunch didn’t take that advice lightly. When the lights hit at 5 a.m. until pitch blackness at 11 p.m., she maximized every last second of every day for 17 years — doing everything in her power to prove her innocence.

In her two years waiting for a direct appeal that ultimately got denied, Bunch lived by the woman’s advice and worked her ass off.

The end goal of exoneration always stood tall in her foresight. Bunch knew in her heart she wasn’t guilty, and much of her time was spent in the prison’s law library, researching and educating herself about U.S. Supreme Court cases, falsified ATF reports, and court transcripts from the wrongly incarcerated.

Coping wasn’t possible; her attention needed to be constantly diverted in order for her inner demons to shut up. Fortunately, at the time, the women were encouraged by the prison to be something different.

Between classes and mastering legal language, Bunch tutored prisoners for their GED exams during her pregnancy. She took a 1500-hour cosmetology course and became a licensed cosmetologist. Through Ball State University, she took college courses and earned her associates and bachelor’s degrees in prison as well.

Training service dogs for nine years, helping mentally challenged prisoners, and being the late-night kitchen cleaner were just a few more ways that Bunch survived her tenure, strictly on commissary. The most she ever made was $3 a day — not even enough for a dozen tampons.

***

The night Bunch went into labor with Trent, medical care had initially refused to see her, writing off her contractions. When they acquiesced, officers escorted her to the prison’s infirmary for a rapid ultrasound. The nurse couldn’t find Trent’s heartbeat.

Guards grabbed and locked two-pound steel rings around Bunch’s ankles and wrists, put her in an ambulance, and rushed her to the corrections sector of Wishard Hospital.

Sporting a bright yellow jumpsuit with “IDOC” printed across the back, Bunch was as reflective as a road sign. Doing her best to not draw more attention to herself, she shuffled into the waiting room — trying not to trip over the trailing silver chain wrapped around her nine-month pregnant belly.

“The doctor came in and I told him, ‘You gotta do something, you gotta help my baby!”” Bunch said. “He started chuckling and said, ‘You’re having contractions every couple of minutes, they’re not going to be able to pick up the heartbeat through one of those microphones — the baby’s fine.’”

The doctor inserted a different microphone and Bunch heard her baby boy for the first time. Trent was delivered via cesarean section, like his brother, and spent a total of 36 hours with his mother before handcuffs and shackles reclaimed their sufferer.

Bunch’s family took Trent home, and she returned to the big house. Her younger brother worked to make sure he had enough gas money every week for his sister to see her son. Bunch saw changes in Trent visit by visit, and she wanted pictures of him every time he came in, but the prison charged a dollar per picture, and her piddly commissary couldn’t afford that many photos.

Her heart ached for Tony and Trent and self-deprecation teased her, but the trek to freedom quickly resumed and reigned supreme.

***

Without an appeal, Bunch spent her days scanning phonebooks religiously — writing and sending out hundreds of letters weekly, begging anyone who looked promising for help.

Some people responded back to her, but most didn’t. The ones that did, attorneys, usually, wanted $25,000 to $50,000 cash up front. Bunch could never ask her family for that; they were taking care of Trent. This cycle persisted until 2001.

Despite her circumstances, Bunch’s good nature guided her in every situation. In 2001, one of her 21 cellmates was pregnant, and Bunch knew all too well about being an expecting mother behind bars, so she routinely brought cookies back for the woman after her shifts in the kitchen.

One day, the woman asked Bunch why she was in prison.

“I didn’t want to tell her, because people look at you different, but she wouldn’t let it go,” Bunch said. “So, I told her, thinking, she’s probably never going to speak to me again. Instead, she said, ‘That’s not you; why aren’t you fighting this?’”

Bunch told the woman that no lawyer had offered to take her case; the woman told Bunch she could change that and wrote to her public defender, Hilary Bowe Ricks. Ricks wrote back asking for a letter from Bunch, and so Bunch made her final plea.

After reading through her trial transcripts, Ricks came to the prison and said the three words Bunch had been waiting five years to hear: “I believe you.”

Finding someone to believe her was only half the battle. Ricks officially came on as Bunch’s lawyer in 2002, but her release took 10 more years.

***

Throughout those years, their team of two quickly became three, then four, and so on. Attorneys and counsel members from the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern, along with fire forensic experts, were just a few of Bunch’s allies who helped uncover the prosecution’s wrongdoings in her 1996 trial.

Bunch realized that she didn’t need science on her side to win when Ricks sent her an article about arson myths. Pour patterns, concrete spalling, and alligatoring were just three of many terms thrown out at her trial claiming to be indicators of arson. The article disproved these claims as arson indicators.

Ricks and Bunch contacted fire investigators who got a woman wrongly accused of arson and the murder of her husband off of death row. They helped reveal new evidence for Bunch’s evidentiary hearing, suggesting that Kinard’s testimony had been greatly flawed all along.

When they subpoenaed ATF files from the original investigation, they discovered that the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Brady v. Maryland, a landmark ruling requiring prosecutors to hand over all exculpatory evidence to the defense prior to trial, had been violated.

The previously concealed documents revealed the amount of heavy petroleum distillate that was actually in Bunch’s trailer: not a single drop.

Accidental spills from a kerosene heater in the trailer’s living room caused the fire. Kinard blatantly falsified a report.

“This man was able to lie and steal 17 years of my life with no accountability. He’s dead — I can never ask him, ‘What were you thinking?’” Bunch said. “They’re allowed to say whatever they want, whether it’s true or not.”

When guards called for Bunch on the day of her evidentiary hearing, she acted surprised. She never spoke about her ploy to freedom with anyone — jealousy often throbs within prison walls.

As they pulled into Decatur County Jail, visions of her petrified 21-year-old-self flooded back. The same guards who arrested her then remained, not treating her any nicer, she said.

Two female prisoners gave Bunch a warm welcome as she shuffled into the women’s cell one last time —she had helped them with their legal proceedings when working at the law library in prison.

Guards made sure Bunch’s cuffs and shackles were tight enough to rub her ankles raw by the time she arrived at the courthouse. After the guards listened to Bunch’s lawyers and heard the new evidence, they walked her back to the van — unshackled and cuffless. One officer told another on the radio to make sure Bunch had a warm dinner waiting for her in two minutes.

Officers continued to treat her like a human being the following days in court.

The judge and prosecution waited as long as they could to deny the motion, saying the new evidence wouldn’t make any difference to her jury. The defense put in an appeal, and Bunch waited two years for an appellate court to decide that, yes — her appeal had merits.

On March 21, 2012, the court reversed her conviction.

In addition, in October of 2020, the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute’s Board of Trustees found that Bunch was eligible for compensation through Indiana’s exoneration fund, by virtue of “clear and convincing evidence” that she had been innocent all along.

“That initial moment, you won everything — you’ve hit the lottery,” Bunch said. “Once the camera is gone and you take a look around, you get smacked in the face with the reality of what you’ve got to overcome.”

***

Before Bunch was incarcerated, she was content walking through life believing that everyone that had something to say was being truthful and that our justice system was fair.

She says forgiveness is easy to talk about, but she’s angry, and she doesn’t think that will ever go away. She can’t erase the time lost with Trent, but the woman she is today wouldn’t ever want to give up the person she is and go back to being that naive girl.

“Obviously, I would give anything to go back and have my kid again,” Bunch said. “But I hope that 21-year-old girl would be proud to know that she discovered she had a voice, that that voice can make a difference, and that lone voice could bring about change.”

Bunch currently works as the Outreach Coordinator for Interrogating Justice. She speaks to people all around the country about advocating for the wrongly incarcerated and urges them to bring about policy change. She shares her story because she knows others need to hear it.

Technically, Bunch hit the exonerated registry when she came home in 2012, but she never got her day in court. She never got to hear “not guilty.”

“To exonerate means you’re unburdened,” Bunch said. “The things that were done to me will never be unburdened; they’re always going to be with me.”

Mina Denny is Indy Maven’s past editorial intern. You can connect with her on Twitter and on LinkedIn.

All of our content—including this article—is completely free. However, we’d love it if you would please consider supporting our journalism with an Indy Maven membership.