In the fall of 2022, I began work on a project I was extremely passionate about but that I assumed would be a one-off. I had no idea that this video I was producing on my nights, weekends, and vacation days – for nothing – would one day become the project I could proudly hang my professional hat on and also use as a touchpoint to get me through difficult times ahead.

In the fall of 2022, I began work on a project I was extremely passionate about but that I assumed would be a one-off. I had no idea that this video I was producing on my nights, weekends, and vacation days – for nothing – would one day become the project I could proudly hang my professional hat on and also use as a touchpoint to get me through difficult times ahead.

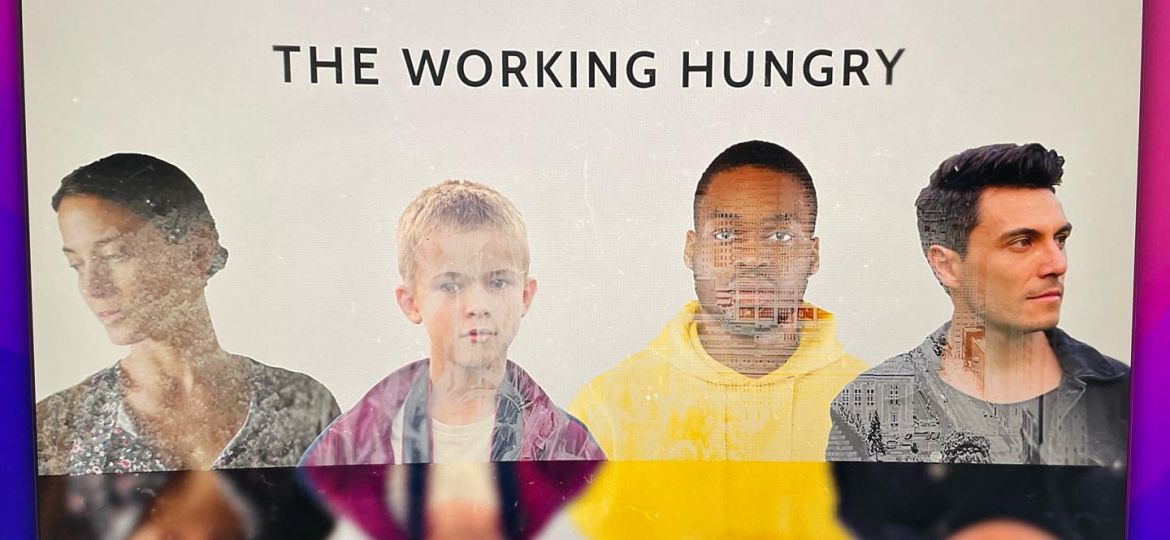

The project was a short documentary called “The Working Hungry.” A small but dedicated team consisting of myself; Dave Miner, a retired Lilly researcher who helped found the Indy Hunger Network; and our videographer/editor David Duncan stretched every penny of donated funds as far as we could to tell audiences what they weren’t seeing: Hoosier families struggling to keep food on the table quite literally work with them, go to church with them, and live in their neighborhoods. The film opened a lot of eyes. It was nominated for a regional Emmy, and spurred more donations for a second film, again highlighting the hundreds of thousands of Hoosiers living with food insecurity every day. We called it “Food, Insecure.”

Words like “hunger” and “food insecurity” are often used interchangeably, but they mean different things. A statewide survey from 2024 of people who have used food assistance found that respondents are infrequently hungry from a lack of food, but identified as food insecure because they have no certainty of where their next meals would come from. In fact, a whopping 90% of respondents said they were food insecure.

Imagine that.

Imagine not having anything edible in your home that you could prepare tomorrow to feed your child. Imagine not having enough money to get gas to go to the grocery or convenience store to buy a box of mac and cheese or ramen or generic breakfast cereal. Imagine not knowing if you could get to a food pantry at a time when it’s actually open because your job schedule is nights and weekends.

These are the people we profiled in both documentaries. And they all work. The first film is called “The Working Hungry” because we didn’t want to engage in the charged debate that can happen around benefits for the non-working. We didn’t need to, because of the over one million statistically food insecure people living in Indiana, approximately 75% of them are employed.

My journey down this path started years ago when I was a daily news producer at WISH-TV. I’m talking last century, Mike Ahern and Debbie Knox days of a local news powerhouse. Over the decade-plus I spent there, I became increasingly concerned about an underlying trend in many of the stories reporters brought back about crime, poor health, and other facets of life in central Indiana: often in the unreported details were hungry children.

There’s something dissonant in being regularly exposed to stories of underfed children in a nation that the USDA says throws out 30%-40% of its total food supply. It was an unsettled feeling I carried with me for years. I still carry it, but now, with new research and new solutions before us, I see the problem of food insecurity with a much greater clarity. “The Working Hungry” was based on the statistics showing that as many as one in five Hoosier kids goes to bed at night not knowing if they’ll have food the next day.

There’s something dissonant in being regularly exposed to stories of underfed children in a nation that the USDA says throws out 30%-40% of its total food supply. It was an unsettled feeling I carried with me for years. I still carry it, but now, with new research and new solutions before us, I see the problem of food insecurity with a much greater clarity. “The Working Hungry” was based on the statistics showing that as many as one in five Hoosier kids goes to bed at night not knowing if they’ll have food the next day.

Each of the films uses the stories of three working families with children, interwoven with expert insights and additional real-life anecdotes, to highlight what many of us living our daily lives fail to see: hunger is rampant among our people, but they’re still bravely fighting that battle every day.

Each of the films is short and offers real solutions to some of the many issues behind food insecurity. We wanted to be clear about problems and equally clear about solutions, so viewers have something to talk about and some real action to take.

I’m sure many of you reading this are familiar with Gleaners Food Bank. Fred Glass, the CEO of Gleaners, is very succinct about hunger: hunger is caused by poverty, and Gleaners is in the poverty alleviation business. Fred Payne at United Way of Central Indiana sees the situation very similarly, with a goal of getting so-called ALICE families distanced from poverty. ALICE stands for Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, but Employed. Indiana has hundreds of thousands of residents who have no assets like home ownership or savings, and work at low-paying jobs.

I’m sure many of you reading this are familiar with Gleaners Food Bank. Fred Glass, the CEO of Gleaners, is very succinct about hunger: hunger is caused by poverty, and Gleaners is in the poverty alleviation business. Fred Payne at United Way of Central Indiana sees the situation very similarly, with a goal of getting so-called ALICE families distanced from poverty. ALICE stands for Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, but Employed. Indiana has hundreds of thousands of residents who have no assets like home ownership or savings, and work at low-paying jobs.

Most of the working hungry in Indiana are employed in jobs – perhaps as many as three such jobs at a time – that do not pay a living wage. When we made “The Working Hungry” film, a living wage for an adult in Indiana was just over $18 an hour. By the time we released “Food, Insecure” a year later in 2025, the living wage had already risen to over $20 an hour. But pay did not increase at a matching rate. A living wage is one that covers basic needs like housing (rent), food, childcare, and transportation, as determined by the MIT Living Wage Calculator. It can vary from region to region within state borders, but make no mistake, there is food insecurity and poverty as deep in rural Indiana as there is in any urban area. (Read down to the bottom to discover what a so-called “comfortable wage” is.)

Experts who understand the impacts of poverty tell us adults working in low-paying roles often lose their jobs because of unreliable transportation and a lack of child care. A doctor in Gary explained to me in no uncertain terms that when families are struggling, food is an afterthought. The nutrition that helps kids grow and keeps adults healthy drops in priority against having a roof overhead and keeping the lights on. Sustained poverty is a recipe for a lifetime of poor health outcomes.

Experts who understand the impacts of poverty tell us adults working in low-paying roles often lose their jobs because of unreliable transportation and a lack of child care. A doctor in Gary explained to me in no uncertain terms that when families are struggling, food is an afterthought. The nutrition that helps kids grow and keeps adults healthy drops in priority against having a roof overhead and keeping the lights on. Sustained poverty is a recipe for a lifetime of poor health outcomes.

Glass, Payne, and many others working in the area of food insecurity understand that solutions will need to come from many different areas. As former state senator and food pantry volunteer Jim Merritt says, hunger doesn’t know political parties. Food insecurity needs to be addressed at the public, corporate, and government levels for the needle to move on a solvable problem.

As I noted, our films offer some real, actionable solutions viewers can feel good about considering when they’re ready to help. Let’s examine a few of them:

- At the personal level, contributing to or working at a food pantry never hurts. Food pantries can’t fix everything, and they’re not intended to be a long-term solution, just an emergent one. However, our team learned that food pantry clients, especially working ones, really do not like having to go to a food pantry for aid. They often feel looked down upon, even though there is no moral failing on their part. In many instances, they will go to a pantry outside of their home area so they don’t have to see someone they know. If you can, donate money to a food pantry or school food assistance program – it goes a lot farther than an actual food donation.

- At the employer level, realize that your employees are not likely to let you know they are struggling with food, and they may not take advantage of an in-house food bank for the same reasons noted above. Some innovative solutions we discovered were factories giving employees “point amnesty,” so emergencies wouldn’t cost the worker their job, and bus passes, so transportation was free and reliable.But what employees really need is a living wage. It can make a huge difference for both the employee and the employer. In central Indiana, EmployIndy has a program called the Good Wages Initiative. It certifies and celebrates employers paying even their lowest income tier of employees a living wage.

- Perhaps the most important place where change can happen is at the policy level. Did you know the reason some good employees will turn down even a minor pay increase is because it will cut them off from benefits they may receive, like SNAP? A policy that allows workers to step away from benefits slowly would make a huge difference to people trying to become self-sufficient. The emergency child tax credit passed during the pandemic lifted 50% of American children out of poverty, until it was repealed. Now the number of kids in poverty is greater than before the pandemic. The good news is, there are already groups working to change policy at the federal level, from reaching out directly to Indiana politicians to supporting national campaigns on behalf of the hungry. You can add your voice.

Finally, what I would really ask is that you think about Indiana’s hungry from a place of kindness. It’s true that there are some folks out there gaming the system, taking free food when they don’t need it, but it’s equally true that there’s more than enough food to go around, and we can’t fret about the few making those choices. Better to focus on making sure a hungry family knows they’re cared about and have resources.

You can watch and share our films from our website, www.workinghungry.org. It allows anyone to stream the documentaries free of charge and has great discussion guides, panelist suggestions, statistics, and resources. If you’d like to host a showing, frequently someone from The Working Hungry team is happy to take part. Just reach out via the site, or DM one of us.

You can watch and share our films from our website, www.workinghungry.org. It allows anyone to stream the documentaries free of charge and has great discussion guides, panelist suggestions, statistics, and resources. If you’d like to host a showing, frequently someone from The Working Hungry team is happy to take part. Just reach out via the site, or DM one of us.

The two films have been shared for public viewing about 200 times over the past couple of years, with many more online streams. At a time when I lost my well-paying job and am still trying to find something comparable, this has been a true bright spot for me. Raising awareness and watching the effects of the shows ripple out is both surprising and rewarding in ways I wasn’t expecting. The support has shown us there’s more to be revealed about food insecurity, and we’re already working on our next piece. It will be a more national documentary on food insecurity among college students. Stay tuned!

Oh, and that comfortable wage for an Indiana resident? A SmartAsset study looking at each state finds that a single Hoosier who wants to “afford hobbies, vacations, retirement savings, education funds, and the occasional emergency,” in addition to the necessities, needs to earn $86,570 a year.

Shannon Cagle Dawson is a longtime multimedia producer and communications expert currently working as a part-time events manager at Christian Theological Seminary. She lives on a historic farm outside Indianapolis with a large flock of chickens. Shannon speaks frequently on mental health issues, particularly suicide awareness, in addition to food insecurity. Find her on IG at @shannoncagledawson, as well as FB and LinkedIn.

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

All of our content—including this article—is entirely free. However, we’d love it if you would please consider supporting our journalism with an Indy Maven Membership.

P.S. Sign up for our weekly newsletter with stories like this delivered to your inbox every Thursday!