“How’d You Get That Job?” is an Indy Maven series where we chat with women who have some of the most unique and fascinating jobs you’ve ever heard of.

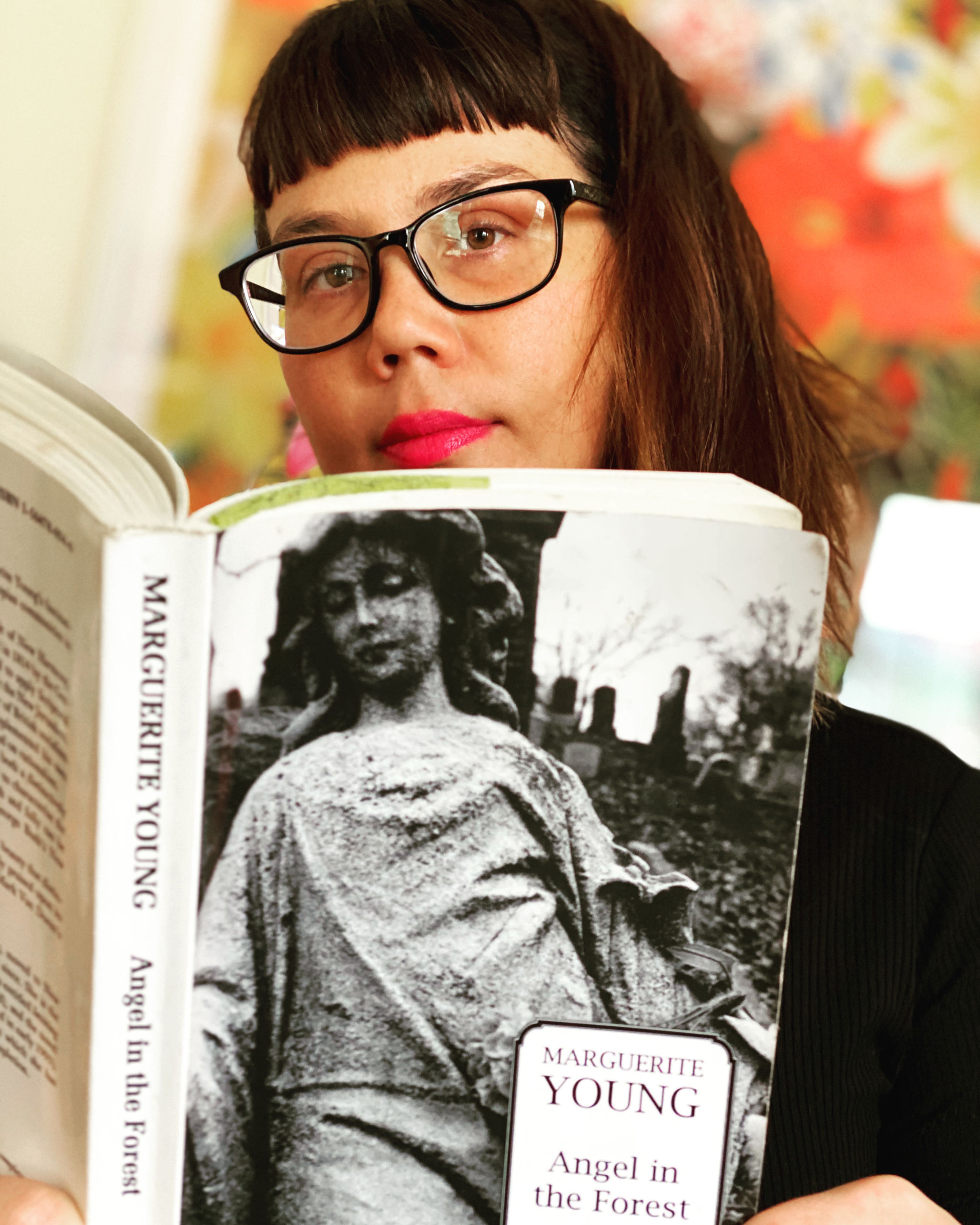

Shauta Marsh is the co-founder of Big Car Collaborative, a nonprofit art and design organization with a focus on building community. She’s a curator, writer, author, and researcher whose work centers largely around cultural and social change.

After launching Big Car with her husband, Jim Walker, in 2004, Marsh went to work at iMOCA (now operating as Indianapolis Contemporary), where she honed her artistic eye and gained invaluable experience in the world of museums and fine art. Now, she’s back at Big Car, overseeing programming and exhibitions at the Tube Factory Artspace in Garfield Park.

In this edition of “How’d You Get That Job?” Marsh shares the ups and downs of her career working in the arts, from how she got started to why it means so much to her to keep creating artistic spaces that are accessible to all.

Have you always been involved in visual arts? When did you know you wanted to make it your career?

Have you always been involved in visual arts? When did you know you wanted to make it your career?

Since I can remember, I thought artists were magic because they could take a thought or idea in their head and make it tangible. When I was younger, I didn’t think of it as a viable career because I like money. It’s typically not a high-paid industry. But more than material things, I value being able to create space for people, the freedom to be whoever I want and to be in a constant state of learning. Working in the arts affords you all those opportunities and to me, that’s worth more than a six-figure salary.

I remember reading the news 12 years ago, all these negative things that were making me question the value and worth of humanity, of myself, too. But a series of experiences with the arts brought me back.

My husband had written a book of poetry, Ripe, and turned it into a play that really affected me. I fell in love with him because of his work as a writer and it reminded me of that. Then, I saw this exhibit at Newfields by Laila Ali. It was like a punch in the gut, in a good way. Then one evening a few years ago, during a show we had at Big Car, this woman came into the gallery and walked right up to me and thanked me for sharing the work. It continued to happen over and over. I realized that art is one of the things that redeems humanity. We destroy and we create. Art makes it happen on a scale we can see.

“Since I can remember I thought artists were magic because they could take a thought or idea in their head and make it tangible.”

Tell us about how Big Car came to life. What were you doing before and when did you know it was time to take the leap into your own venture?

There was a group of us all chipping in $10 a month for a shared studio at the Murphy Arts Center. Philip Campbell was always very supportive of artists and offered us a 1,200-square-foot space. We wanted something fun to do. There weren’t many events, especially in Fountain Square in the early 2000s. We started having poetry readings and hosting art and music shows. But all this was costing us more than we could afford so we started a 501c3 and began applying for grants.

We helped Phil with Masterpiece in a Day and started to see how art and public events brought the community together—and it grew from there. We wrote grants, did the accounting, press releases, and organized shows. We learned trial-by-fire how to run a non-profit. Big Car continued to succeed and grow. But I lacked confidence and for the most part, people just saw me as Jim Walker’s wife.

Then, in 2009, Jeremy Efroymson was looking for help with iMOCA, so I was his assistant for two years. I learned how museums work, about the high art world, and then Efroymson handed it off to me in 2012. I was there until 2015 as executive director. In 2015, Big Car purchased the Tube Factory campus and I returned to work with Jim. He regards me as equal to him and we passionately agree and disagree about all sorts of things. He’s my favorite artist.

Was there ever a show you curated or an event you helped organize when everything clicked and you thought, “This is exactly what I’m supposed to be doing”?

The LaToya Ruby Frazier and Tony Buba exhibit was a big deal for me. I had that same punch in the gut feeling about Frazier. That exhibit drew over 1,200 people, some were in tears. Frazier’s work was autobiographical and was dealing with her grandfather’s terminal illness—the effect of the steel industry in Braddock, Pennsylvania, loss of factories, hospitals, quality health care, identity, and race.

The people who saw it kept coming back, started donating, and we were able to get a Warhol grant. That show kicked off a series of blockbuster artists for me as a curator. This show was the beginning of me having faith in myself and what I thought. Frazier went on to win a MacArthur Genius grant. I was on a roll.

What about the opposite? Can you talk about a time when you felt discouraged or worried you were on the wrong path?

When I was on this roll of success as a curator and executive director at iMOCA, I went through a professional crisis. I had just received a grant. The other recipients and I were going around the table talking about what we do, the change we make: One organization helped pay for surgery for blind children and babies; another built wheelchair ramps. I was the only arts organization. My turn came and I was like, “I put on art exhibitions.” It felt so unimportant.

Then, I was driving home one evening and I see this woman at a bus stop, crying, no shoes, in a spaghetti-strap top. I stop and pick her up and drive her to a house. I asked her questions. She said nothing to me. I felt utterly helpless and useless. Living in the city you see all this need all the time. Some people have learned to ignore it. I never have been able to. It felt like all that success for me was stupid…so what? This feeling went on for months.

Then one day, the woman I gave a ride to comes into iMOCA. It was a storefront space and she saw me, so she came in. She thanked me for giving her a ride. Then she says “I don’t belong here. I didn’t graduate from school.” I said, “Yes, you do.”

She didn’t want to talk about herself, but she wanted to talk about the work. It was the Toyin Odutola exhibit. I realized then there’s so much pain and suffering in the world, money isn’t the only thing needed. People need self-confidence, power, and agency. The arts help with that. So, this is my small contribution to the world—an attempt to create space for people. I can’t turn back from that, from the feeling I get when people see something that moves them in a way they don’t have the words for. Also, it’s okay to hate art. All feelings, ideas, and meanings are valid.

What do you see or hope for the future of art in Indianapolis?

I hope there will be more financial support for the arts and artists—that our city could start seeing artists as valuable.

What’s your advice for other women who want to make a positive cultural and social impact in the city?

The best advice is from Kenny Roger’s The Gambler, “You got to know when to hold them, know when to fold them, know when to walk away, know when to run.”

Photo: Jim Walker

Ally Denton is a regular contributor to Indy Maven.