All month Indy Maven will be partnering with Indiana Humanities to shed some light on women of the suffrage movement here in Indiana and beyond. March is Women’s History Month and 2020 marks 100 years since (white) women were given the right to vote in our country. Stay tuned for many more interesting stories about the women who helped secure our rights.

When we talk about the suffrage movement, the images that come to mind are middle-class white ladies in poofy hats. It’s also true that many national suffrage leaders did not support equal rights for African Americans. And depending on where you lived, if you were African American, Asian American or Native American, local racist laws barred you from voting in 1920. Yet in Indiana, historians are uncovering a story that veers from the popular images and national narrative in several important ways. We’re discovering the long history of black women’s activism, as well as the intersectionalist ways that Black women advocated for suffrage, economic freedom, and civil rights.

From the beginning, the Indiana suffrage movement was integrated; Black women attended suffrage conventions throughout the 1850s. One, unnamed in the records, even asked the white women if they were talking about her right to vote—and she was told yes! Naomi Bowman Talbert Anderson toured the Midwest in the 1860s and 1870s, calling for equal rights regardless of race or gender, as well as prohibition of alcohol, which she and many other suffragists felt would prevent the horrors of domestic violence.

Evansville’s Bettiola Fortson was a suffragist—and a hatmaker and a poet. Like a lot of African Americans in the 1910s, she moved to Chicago, where she got involved with the Alpha Suffrage Club, founded by Ida B. Wells. Fortson was the second vice president of the Alpha club, widely considered the nation’s first Black women’s suffrage organization.

In 1912, Branch No. 7 of the Equal Suffrage Association was founded in the home of Madam CJ Walker. Branch No. 7 was the first suffrage organization in Indianapolis led entirely by Black women and men; African American branches are also documented in Terre Haute and Marion, and other clubs around the state had black members. Carrie Barnes Ross, a public school teacher who was active in the NAACP, served as Branch No. 7’s first president. “We believe,” she wrote, “that colored women have need for the ballot that white women have, and a great many needs that they have not.

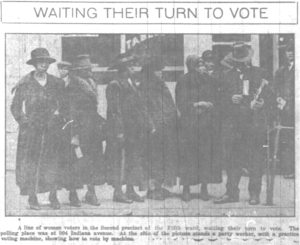

And last but not least—Black women showed up to vote. We know from records that Black women rushed out to register to vote as soon as they were able; in Columbus, the very first women in the county to register were black. In 1920, turnout in black precincts was high, and we also have at least one photo of Black women waiting in line to vote.

And last but not least—Black women showed up to vote. We know from records that Black women rushed out to register to vote as soon as they were able; in Columbus, the very first women in the county to register were black. In 1920, turnout in black precincts was high, and we also have at least one photo of Black women waiting in line to vote.

These are tantalizing traces of an important but overlooked history. Dr. Anita Morgan at IUPUI received a May Wright Sewall Fellowship to do more research on black suffragists in Indiana. This fall, a new book about Black suffragists, Vanguard, will be published, and Indiana Humanities will be sharing as we learn all year long on @INSuffrage100. We hope you follow along as we discover and share the stories of the diverse women who fought so long and so hard for equal rights.

Leah Nahmias is the Director of Programs and Community Engagement for Indiana Humanities.